ED 5131 - Assignment 1, Post 3: Being intentional about digital well-being

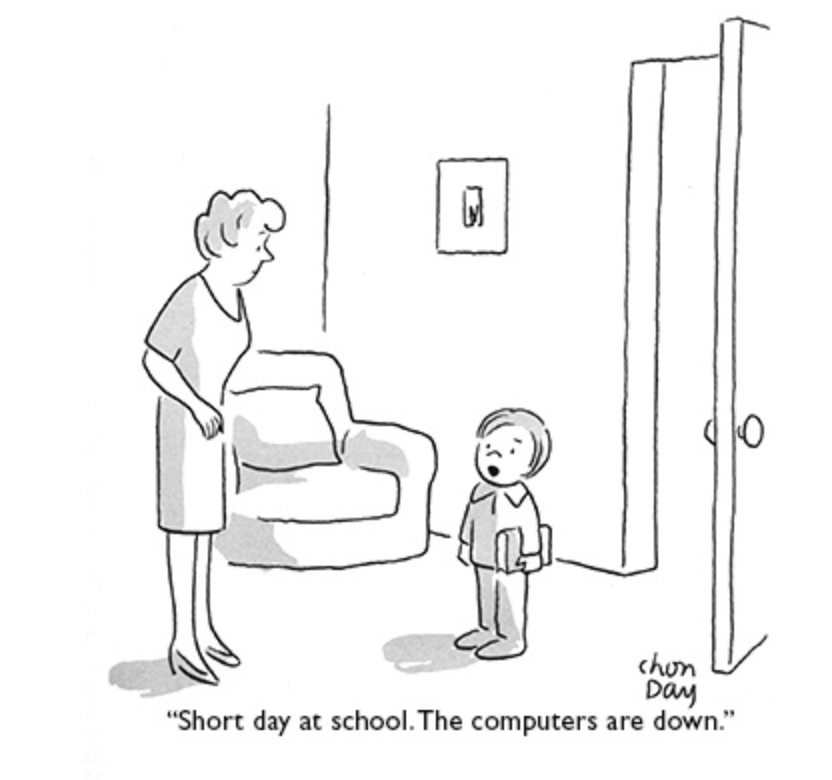

Day, Chon. (1985). “Short day at school. The computers are down.” New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.art.com/products/p35073706435-sa-i9429288/chon-day-short-day-at-school-the-computers-are-down-new-yorker-cartoon.htm

This week’s theme of digital well-being reminded me of a study by Montemurro et al. (2023) that I recently read on the impact of well-being initiatives overall. While this study didn’t deal with well-being specifically in a digital context, the emergent themes that the researchers identified could be applied to our understanding of digital well-being.

Theme 1: Student and staff well-being are interconnected

Resources from the Cyberbullying Research Centre demonstrate an approach that is designed to be proactive and preventative as opposed to reactive. And with good reason! While building an anti-bullying culture is challenging, teaching prevention is more effective in the long run. This is reflected in the findings of Montemurro et al. (2023), who note that educators have feelings of being “stretched thin” as a result of having to “teach and manage complex needs of students,” thus leading to higher instances of burnout among staff (p.8).

What I can draw from this is that well-being (digital or otherwise) has to be approached with intentionality. While the Cyberbullying Research Centre provides educators and parents with activities that address issues related to cyberbullying and digital well-being, these types of resources have to be used as part of a broader strategy that involves the whole school.

In my personal practice, a code of conduct that does not provide in-depth considerations for cyberbullying creates challenging conditions for addressing behaviour: students are not aware of expectations, parents are not aware of consequences for misconduct, and school staff have few mechanisms by which to concretely address misbehaviour. While it is possible to deal with issues on a case-by-case basis, this can lead to uneven application of the code of conduct. In other words, consequences can be seen as too severe, or not severe enough (depending on the stakeholder that you’re asking). At the very least, the end result is frustration from everyone involved, and at the very worst, increased administrative workloads and unaddressed behaviourial that affect entire classes, and ultimately burnout for classroom teachers.

Ultimately, a well-written technology policy should be created alongside the school’s code of conduct. But it doesn’t end there! This year marked my second year as the IB DP coordinator at my school, and revisiting our policy documents (code of conduct, academic integrity, admission, assessment/evaluation) reminded me of why policy reviews are in place: policies aren’t static. They’re living documents that reflect the context and time in which they are written. Given the speed at which technology changes, policy reviews should be consistent and timely. Creating scheduled reviews is one of those things that will help schools remain proactive as opposed to reactive, and in treating policies as living documents, schools will be able to ensure a proactive approach to addressing issues before they become issues.

Theme 2: Well-being is holistic and requires balance

This theme was a significant one for me because it’s easy to make the mistake of treating digital competency education as a second thought, perhaps because of the myth that digital native = high digital literacy. Research by the ICDL (2014) indicates that digital native implies high digital competency; however, digital competency in youth remains low, resulting in a “lack of critical and participatory literacy”. Respondents in Montemurro et al.’s (2023) study indicated that well-being took many forms, including “physical, mental, social, spiritual, environmental, [and] financial” and is an act of “honouring the whole person and all aspects that make you feel healthy and well” (p.4). If we extend this thinking to include the digital domain, the approach to digital well-being in schools needs to be conceptualized in the same way we think about other domains of well-being - as one part of a big whole whose pieces work together to affect an individual.

So where does this leave us? I’d say as educators, there’s a ways to go as far as our current conception of digital well-being goes. There has been progress, as literacy curricula like Google’s Be Internet Awesome are engaging students in thinking about the emotional impacts of their communication online; however, I get the sense that this field of digital competency is still emerging. We’re certainly aware of the negative effects that overuse or misuse of digital tools can have, but the challenge lies in taking a proactive, uniform approach to ensuring that issues are addressed before they become issues.

Bibliography

Montemurro, G., Cherkowski, S., Sulz, L., Loland, D., Saville, E., & Storey, K. E. (2023). Prioritizing well-being in K-12 education: Lessons from a multiple case study of Canadian school districts. Health Promotion International, 38(2), daad003. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daad003

Day, Chon. (1985). Short day at school. The computers are down. [Cartoon]. New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.art.com/products/p35073706435-sa-i9429288/chon-day-short-day-at-school-the-computers-are-down-new-yorker-cartoon.htm